Micro

At the micro level, grey zone influence is predicated on the observation that influence involves people. It follows that insights from the science of human thought and behaviour (psychology) and the sub-discipline that relates to how thought and behaviours are influenced by the real, implied or imagined presence of others (i.e., social psychology) may offer pertinent insights into the processes through which interactions between people shape thoughts, feelings and behaviours to ultimately effect or stymie influence (Turner, 1991).

Situational awareness and social influence: what type of influence?

Although grey zone or malign influence is often discussed as a single phenomena, the psychological literature highlights subtle differences in the nature and goals of influence, the form of influence, as well as its effects on the target. Delineating these is key to an initial assessment of influence and grey zone situational awareness. Table 1 provides an overview of the different forms of social influence. It can be seen that influence differs based on its goals (shape an initial response; reinforce a response; change a response; Miller, 2013), targets (can target thoughts, feelings or behaviours), the form of influence (informational or normative; Turner, 1991) as well as its effects on the audience (from private, internalised acceptance to public superficial conformity; Kelman, 1958).

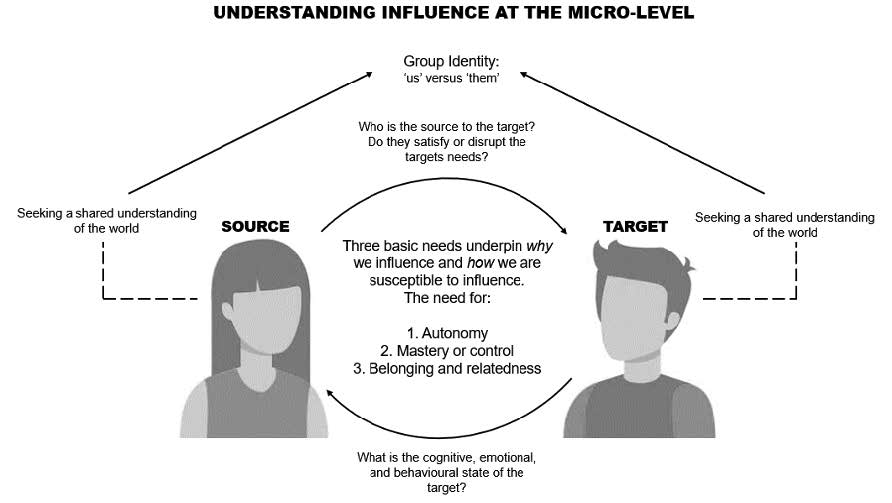

It is clear from the above that influence is multifaceted. Its effects are shaped by aspects of the audience (or perceiver), the characteristics of the influencing agent, as well as the broader context in which at an influence attempt is delivered and interpreted. To understand influence at the micro level, we look to how influence is conveyed: from a source to an audience, characteristics of the audience, as well as the interaction between the two. Figure 1 provides a summary overview of the key principles of this section.

Table 1. Overview of different goals, targets, forms and effects of social influence.

|

Goals of Influence |

Definition |

|

Shape an initial response |

Occurs when people have no prior knowledge of the topic; do not have an existing pattern of responses relating to the topic. |

|

Reinforce a response |

Aims to strengthen already held convictions and patterns of behaviour. |

|

Change a response |

Seeks to alter already established patterns of behaviour. |

|

Targets of Influence |

Definition |

|

Cognitions |

Influence that attempts to target people’s thoughts or attitudes. |

|

Emotions |

Influence that attempts to target people’s emotional responses. |

|

Behaviours |

Influence that attempts to directly shape people’s behaviours. |

|

Form of Influence |

Definition |

|

Informational influence |

Influence attempts that seek to provide evidence of reality “how things are”. |

|

Normative influence |

Influence attempts that seek to provide evidence of the opinions, beliefs or expectations of others. |

|

Effect on the Audience |

Definition |

|

Private “true” acceptance |

Occurs when people internalise (take on) and accept the desired response, and enact it privately. |

|

Public conformity |

Occurs when people publicly appear to hold particular attitude or behavioural stance but privately believe something different. |

Social influence is shaped by basic psychological needs

Figure 1 shows that central to understanding influence is to appreciate how it interacts with basic psychological processes and needs. There is broad agreement within the psychological sciences that people are driven by three fundamental basic needs: the need to have mastery or control over one’s environment, the need to belong, and the need to be autonomous (see also Deci & Ryan, 2000). Table 2 provides an overview summary of the needs and their application to the grey zone context. Each of the needs locates and discusses the psychological processes of influence through a different lens. Specifically, the need for mastery reflects a need to form accurate opinions about ourselves and the world around us. This need is primarily related to how aspects of cognition (i.e., people’s internal thought processes) shape how people seek out, and respond to, information in the world around us. The need for mastery treats influence as a primarily cognitive phenomenon (in the minds of the individual person or audience member). Yet, influence is not purely informational in character. Its effects are shaped by and also shapers of our sense of how we fit into the world; who “I am” and who “we are” (i.e., identity) and who “we” stand with and against. The fundamentally social aspect to influence is therefore reflected in the need to belong, whereby group memberships and identities determine who will be listened to or dismissed, how information is processed within and between groups. Finally, influence in the grey zone is about a contest for power and power often constrains free will. Our analysis of the need for autonomy reflects how influence attempts may be seen to impede the need to act with self-determination, with implications for how deeply internalised any resultant attitudinal or behaviour change may be.

In the sections that follow we expand upon the basic arguments anticipated above and reflected in Figure 1. The overriding proposition is that people will be motivated to pursue goals and relationships that allow them to fulfill the basic need for mastery, belonging and autonomy (see also Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). As such, these needs relate to both the processes that make people susceptible to influence (i.e., speaking to our nature as fundamentally social beings), as well as helping to explain why we want to influence others (i.e. to change the thoughts, perceptions, attitudes, perceived norms, and behaviours of others). We adopt the basic needs as a framework to organise the current and most credible evidence on this topic from the psychological sciences.

Table 2. Overview of basic needs, definitions and relevance to grey zone influence.

|

Basic need |

Definition |

Relevance to grey zone influence |

|

Need for mastery |

Subjective feelings of competence and control within one’s environment. Reflects a need to form accurate opinions about ourselves and the world around us. |

This need shapes the functional effects of informational influence – people are susceptible to informational influence (and seek to influence others, in turn) because it aids the mastery need. |

|

Need for belonging and relatedness |

People have a need to feel connected to others and to be part of groups which give them positive self-value (self-worth). |

This need shapes the fundamental effects of normative influence – people are susceptible to normative influence (i.e., care what valued others think and expect) because they want to maintain their valued relationships and commitment to groups. |

|

Need for autonomy |

People have a need to feel like a causal agent with respect to their own actions. |

Influence attempts which appear to be coercive or constraining of an individual’s (or group’s) free will, may produce reactance and be counterproductive. “True” (private) internalised attitude change is fostered where the influence is experienced autonomously. |

Social influence is shaped by the need for mastery

People have a fundamental need for mastery – that is, the need for a subjective feeling of competence and control within their environment (Table 2). The need for mastery reflects a need to form accurate opinions about ourselves and the world around us. This universal need for mastery can also differ in intensity between people (i.e. it is shaped by an individual differences component) and is achieved differently in different situations (i.e. there is a contextual component). These factors mean that the way that we achieve mastery may differ between people and across different situations, as outlined below.

People all have a fundamental need for mastery, that is, the capacity to understand, make sense of, and predict their environment.

People can differ in the degree to which they need/seek mastery

Although all people are motivated by a need to organise and understand the world around them in a way that generates meaning, people can differ in the degree to which they are motivated to access and process information. One of the most extensively researched ways that this has been conceptualised in the literature on persuasion is as an individual difference in need for cognition. Need for cognition captures the extent to which people are inherently interested in and enjoy effortful cognitive activities (e.g., Cacioppo et al., 1996). People high in need for cognition have a greater tendency to gravitate towards in-depth argument and reflection to make sense of the people and world around them (akin to what Pennycook et al., 2015, refer to as analytic thinking). On the other hand, people who are relatively lower in need for cognition are more likely to rely on others as well as cognitive heuristics (rules of thumb or short-cuts) to achieve this need (akin to intuitive thinking; Pennycook et al., 2015).

Need for cognition and thinking styles (i.e., a general tendency to use more analytic modes of reasoning) may shape the goals, type and effects of influence outlined in Table 1. For instance, people higher in need for cognition may be more attentive to and influenced by (well-constructed) informational influence, while people lower in need for cognition may be more susceptible to normative influence (as a heuristic; see Table 1).

The tendency to enjoy effortful cognitive tasks also shapes the degree to which people internalise and accept the message in a way that is deep and enduring. There is some evidence that the attitudinal change that occurs for people higher in need for cognition endures over time (Haugtvedt & Petty, 1992). The same study also reported that, when a counter message was presented after the initial persuasive message, people high in need for cognition displayed attitude resistance, while people low in need for cognition accepted the counter message and reverted to their initial attitude (Haugtvedt & Petty, 1992). There is some evidence that mood affects whether or not people are motivated to engage deeply with messages: people in a positive mood process messages in a way that will lead them to maintain that positive mood (i.e., they will process deeply if the message is positive but superficially if the message is seen as negative or threatening; see Hullett, 2005).

The mechanics of influence can differ for people based on differences in how they think. People who inherently enjoy more effortful cognitive activities and routinely adopt more analytic modes of thinking will be more motivated to deeply engage with messages while people who adopt more intuitive “gut-feel” modes of cognition will be more influenced by heuristics.

Well-designed influence strategies should consider that some people will process the information deeply and systematically (high effort), while others will process the message relatively quickly and superficially (low effort).

Deep versus superficial processing: fulfilling the need for mastery under different conditions

What is the mode or medium of the influence attempt? How much time will the audience member have to engage with the message? There are some situations and contexts that lend themselves better to achieving mastery goals than others. The most prominent and extensively researched model of persuasion is the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The elaboration likelihood model suggests that, influence/persuasive attempts are shaped by time and opportunity to engage with the message. The insights of this model suggest that the affordances of the influence setting or context are likely to shape the form of processing that takes place and, in turn, how mastery needs are satisfied.

When a person has time and capacity to process a message deeply, this is associated with a central processing route. Central route processing involves high effort and thoughtful consideration of the message presented, as well as its relation to existing knowledge. Effective cognitive or behavioural influence via the central route is dependent on the quality of the information presented, and the influence itself tends to be more enduring (i.e., more deeply internalized per Table 1; see Petty & Cacioppo, 1986).

On the other hand, where a person does not have the motivation or time to process an influence message deeply, then peripheral processing occurs. The peripheral processing route is reliant on cues and heuristics present within or relating to the message (i.e., repetition, attractiveness of the source, norms; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). When engaging in peripheral processing, people do not attend to the substantive argument of the message but instead rely on accessible cues from the message to form a judgement.

Influence works differently in different situations or media. Conditions that offer the opportunity for deep engagement (e.g., conversations) will tend to be associated with central processing and will therefore need to present high-quality arguments to be successful. Conditions that do not provide people time or opportunity for effortful processing (e.g., online media campaign) will be associated with peripheral processing, in which case heuristic cues will be more influential than presenting deep argumentation.

Heuristics and peripheral cues are therefore key to many influence campaigns (including online campaigns) although the online environment may well have a balance or both central and peripheral processing (SanJosé-Cabezudo et al., 2009).

Table 3 provides an overview of eight common types of heuristics relevant to peripheral processing and their application to grey zone influence (adapted from the work of Cialdini, 2001). While peripheral processing may be more relevant to situations of mass exposure and influence, it is conceptualised as a lower effort route to decision making and thus tends to be less enduring. In peripheral processing, the content and presentation of the message itself is significant. As summarised in Table 3, messages containing moral-emotional language (e.g., words like ‘honour’ and ‘hate’) increase the spread of moral ideas amongst ingroups, increasing the opportunity for influence (Brady et al., 2017). As such, emotion targeted influence may be a more powerful source within social groups than mere cognitive influence. Furthermore, some limited studies suggest disinformation and misinformation can spread easier and faster than factually correct information (Vosoughi, Roy & Aral, 2018). Emotional reactions to true and false news may differ (Vosoughi et al., 2018), once again highlighting the effects of emotions in influence campaigns.

Importantly, social media tends to provide heuristic rich information: longer posts may be more persuasive (even if they are inaccurate), those posts with more “likes” convey a norm or consensus of opinion that people may use to inform their own decisions.

Table 3. Summary and overview of common heuristics and application to grey zone influence.

|

Heuristics |

Definition |

Application to grey zone influence |

|

Emotions (direct and indirect) |

‘Mood as information’ – emotions can act as positive or negative cues guiding judgements and evaluations. This can occur directly (i.e., some objects/experiences are already linked to a specific emotion through association/experience) or indirectly (if one is in a positive emotional state, they are more likely to hold favourable opinions and vice versa). A ‘good mood’ also decreases likelihood of critical engagement with information. |

Emotive messages will cue particular appraisals (understandings) of the situation more effectively than cold cognitive messages. |

|

Attractiveness/liking |

Attractive people are often perceived as being more likeable, trustworthy, and intelligent by increasing positive affect. People also tend to agree more with those they like; this may not only include attractive people, but those who look like and think like them. |

Attractive and/or likeable sources (e.g., ‘influencers’) are likely to be more effective agents of influence. |

|

Familiarity |

The ‘mere exposure effect’ – when information is presented repeatedly (and from multiple sources), people become more likely to accept it. A consistent source is more persuasive. |

Repeated exposure to a message from the same and/or different sources will exert greater influence, despite the strength of the content. |

|

Expertise/authority |

People tend to associate authority figures with having correct opinions. |

Messages ostensibly presented by an authority or authority figure will be more influential than those which do not. |

|

Message length |

Longer written messages are perceived as being more valid or “correct”. This invokes the feeling that the justification/argumentation is more extensive. |

A longer message can be more persuasive than will a short message. |

|

Consistency |

The ‘foot-in-the-door’ technique. People tend to want to want to behave in a way that is consistent over time. Deferring to pre-existing opinions not only reduces doubt but provides guidance as to how to respond to future events. |

People are likely to comply with a request if they have already complied with a smaller request. |

|

Scarcity |

Resources that appear to be becoming scarce or more difficult to attain become more attractive. |

A message or opportunity delivered under time pressure may be more influential than one that is longstanding/available. |

|

Consensus |

‘Social proof’ – we look to what the majority view is in order to inform our own stance. |

Communicating that a majority supports a particular position will be more influential. |

Our analysis thus far has focused on the cognitive underpinnings of influence in terms of the attributes of people (i.e. their need for cognition) and particular situations (i.e. whether the situation would allow for deep or superficial processing). This analysis treats influence as a primarily cognitive phenomenon (i.e. linked to our internal thoughts and need to feel competent in our environment) but does not adequately address the social and relational aspects of influence. Influence, after all, is not just about changing thoughts – it is about reshaping people’s definitions of the world and their place in it. With this observation in mind, the next section complements the focus on the cognitive to more deeply consider the social bases of influence.

Social influence is shaped by the need to belong

Humans are motivated by a need to belong, that is, the need to seek and maintain strong relationships with individuals and groups (Leary & Baumeister, 1995). One of the primary ways in which this sense of belonging has been conceptualised and studied in the psychological sciences is through the lens of identity. Although people often think of themselves as unique or idiosyncratic individuals there are many contexts in which people think of themselves in terms of group memberships with a shared social identity. Thus, identities exist at multiple levels of abstraction: they shape who we are as idiosyncratic individuals (“me and I”; individual identity), but also as members of groups (“we and us”; social identity) and even members of the human race (human identity; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). These identities become relevant in different situations implying that identity is relevant at all levels of analysis (micro, meso and macro). From this broad approach are derived two primary implications about the nature and effects of influence.

People have a fundamental need to belong, that is, a need to have and maintain relationships with other people and groups. This need to belong is often expressed via commitment to groups, that is, social identification. Group memberships (“we and us”) can become the lens through which we perceive the world. Under these circumstances, social or group identities are far more important to understanding collective behaviour than cognitive or idiosyncratic attributes.

Influence occurs within and between people who share a group membership (identity)

A social identity analysis of influence places group memberships at the center of social influence (Turner, 1991). Our analysis above touches on the idea that one of the ways that people can achieve a sense of control and mastery of the environment is to know what relevant others believe and do (i.e. the consensus heuristic; Table 3). In fact, the situation is more complicated than that because while people are motivated to do and say the “right” things (reflecting an ostensible mastery need), they are also motivated to share an understanding of the world with the people around them reflecting a relatedness need (Festinger, 1954, see Figure 1). In this way, mastery needs interact with relatedness needs to shape who is listened to and accepted as appropriate sources of the world around us.

A key insight derived from the social identity approach is that ingroup members (that is, people with whom we share a social identity) are more persuasive than outgroup members (McGarty et al., 1994). Put differently, it is primarily where source and target share an identity (a social categorical relationship: “us” versus “them”), that influence will be mutual and will flow within the group (intragroup). Importantly, this is not a cognitive short-cut or heuristic in the terms considered above (Table 3). Such identities become a basis for perceiving a shared reality and in doing so are key to meeting mastery needs but also act to foster our sense of who we are, who we stand “with” and “against” (belonging need). A key implication is that, if in that context, the source of the message/influence is perceived to be an outgroup member, then they will be seen as less subjectively valid sources of “truth” than would an ingroup member.

People with whom we share a social identity (ingroup members) are seen as more important and valid sources of reality than are outgroup members. Conversely, information can be discredited if it is seen to come from an outsider. Influence can gain greater traction when it appeals to a common sense of “we” and “us”. Grey zone situational awareness should seek to identify and describe the group memberships at play in each situation to map the fault lines of influence.

Group norms shape “our” values and how “we” can be persuaded

A second implication is that when a group becomes salient or relevant in a particular context, group members take on the norms, values and perceptions of the group in that context (Turner et al., 1987). When a given identity is salient (meaningful, relevant) to a context, people self-stereotype and in doing so take on group norms for how “we” think, feel, and act – in this way, our thoughts (cognitions), feelings (emotions), and actions (behaviours) are socially influenced (Thomas et al., 2009). If I am at a sporting match then my identity as a supporter of a sporting team is likely to be more relevant to shaping my perception of the group memberships in that situation. The sporting team identity will also be associated with normatively prescribed behaviours (jumping up and down, calling out), emotions (elation when we win, frustration when we lose), and beliefs (the referee is against “us”). If I am at work then my professional identity becomes relevant and my perceptions of what is normatively accepted and valued within that professional context will shape my values, feelings and behaviours (working quietly, attending meetings). Thus, group memberships are a primary way in which social influences “out there” shape and affect mass behaviour as a form of persuasive influence (Turner, 2005).

Social identities are linked to group norms, that is, informal rules that shape emotions (what “we” feel), cognitions (what “we” think”), values (what “we” value) and beliefs (what “we” believe) of group members. Group norms explain why group members act in ways that are similar to each other but different to members of other groups. An effective way of exerting mass influence (across members of a group) is to shape the norms of the group.

A further important implication is that identities and norms in combination act to buffer the group from outside interference but also define “our” attitudes and values. It is well known that attitudinally congruent messages tend to be more influential than attitudinally incongruent messages (e.g., Taber & Lodge, 2006). The social identity account helps us to understand why this is the case: attitudes and values are both cues to the identity of the source (Hogg & Smith, 2007) – when someone relays a message or value that is inconsistent with one’s own group then they are immediately perceived as an outgroup member and their message is disregarded. Indeed, people are sensitive to cues that denote the membership of message sources, even in relatively anonymous environments (e.g., online; Lea, Spears & de Groot, 2001). On the other hand, where messages are tailored in such as a way that they align with the underlying attitudes and values that are held to be important by group members, they tend to be more successful. For instance, Luong et al. (2019) framed messages about fracking in a way that drew upon liberal and conservative values (respectively) and found that messages that adopted liberal language and values were more persuasive with liberal group members and messages that adopted conservative language and explanations were more persuasive for conservative group members.

Language provides important cues to identity. Messages that are crafted to draw upon (align with) the subjectively important values and attitudes of group members will be more influential than messages that use language of the outgroup or authority.

Such group norms also define who may be listened to as “an authority” and who is not. Returning to the example above, a fan of a sporting team would not be influenced by the football tips of a work colleague (who has no expertise on that topic) but that same colleague may be a source of influence in a work setting when that professional identity and its associated norms are salient. Turner (2005) argues powerfully that there is no way of determining the validity or value of information independent of the social context in which it is perceived. He suggests (p.3):

“The same information which persuades one group will fail to persuade another. One group’s expert is another’s crank. One does not accept influence from experts because of the information they provide (if one is not an expert, how can one judge its quality?), but accepts the information as valid because one defines them as an expert….” Building upon a de-contextualised analysis of influence as a display of “facts” or mere information from a source to a target, Turner (1991) suggests that influence is primarily about who is defined as an expert versus not and these definitions stem from the group memberships that are at play in that situation.

Finally, group norms also shape how information is shared and debated within a group, and the level of critical engagement with content per se (Levine, 2018). For instance, Postmes et al. (2001) demonstrated that groups can differ in the degree to which they emphasise the reaching of agreement (consensus) versus critical engagement. Groups that see critical engagement as important to “who they are” tended to make better decisions than those groups who endorsed consensus norms.

Group norms affect who is deemed to have authority (or not) and also help to determine how information is processed within the group (e.g., some groups emphasise “critical thinking” or not being a sheep as a defining aspect of their group membership). A particular narrative or influence message will be more influential if it adheres to the ways that group members typically regulate the flows of information within the group (e.g., telling a leader, elder or ruler before other people are consulted).

We seek agreement with the groups we are a part of, establishing social norms by reaching collective agreement (consensus). The cumulative insights of the mastery and relatedness sections then lead to the conclusion that cognition (thought) and social influence are inextricably linked.

Social influence and the need for autonomy

The need for autonomy reflects the basic need to feel that one’s decisions are self-directed and self-determined (Ryan & Deci, 2000). As seen in Table 1, influence functions as a means of social forces exerting beliefs, opinions and values (normative influence) and evidence of reality (informational influence) onto one another in search of agreement, ultimately leading to changes in thoughts, emotions and/or behaviour. However, any such (informational or normative) influences will be bounded by the degree to which people feel that they are encountering a message or influential agent of their free will, versus via coercive means. In this respect, people want to feel that they are playing an active role in the selection, exposure and (possibly) exchange of information. Linking with our analysis of identity, this need can exist at the level of the person (i.e. personal identity, see Ryan & Deci, 2000) but also exists in terms of the autonomy and self-determination of people as group members (Thomas et al., 2017). An analysis of the need for autonomy in the influence domain, then, points to an additional key element: it is necessary to further examine the power dynamics and relationship between a source and audience to understand the nature and effects of influence.

People have a fundamental need to feel that their individual and group interactions and decisions are self-directed and freely chosen. People are likely to be more open-minded to influences that are invited relative to those that have been encountered via force.

Legitimate authority and coercive power.

Turner’s (2005) three-process theory of power suggests that there are three paths to power (defined as akin to influence, getting people to do what one wants). Our analysis of the need to belong highlights that group members will freely and autonomously take on the norms, values and attributes of groups to which they are identified and, in that way, group members can shape what is seen to be real and true. This is the path for persuasion-based influence – power through people rather than over people. However, his three-process theory of power suggests that there are two other paths: one based on authority and another based on coercion.

Authority can be understood as the capacity to influence because people believe that it is right and appropriate for this person, organisation or institution, to exert influence on certain matters. Inherent to this definition of authority is that people will voluntarily comply with the decisions of authorities where those authorities are deemed legitimate (Tyler & Lind, 1992). Legitimacy refers to “the belief that authorities are entitled to be obeyed” (Tyler, 1997, p.323). Legitimacy is particularly important because a legitimate authority will be obeyed without rewards or the threat of punishment per se. Indeed, for influence to be accepted and internalised as a deep, privately held conviction (see Table 1), authorities must establish a sense of legitimacy in terms of their relationships with groups and group members.

However, ‘legitimacy’ is an attribute that one can make about authorities or leaders. Linking with our points above, who is deemed to be a legitimate authority is itself a product of influence, because it is itself based on norms that a specific person, role or group has the right to prescribe attitudes or behaviours (Turner, 2005). The degree to which an authority has the right to prescribe private beliefs will also depend on the nature of the group and the scope that it affords the authority in question. Importantly, this form of authority-based influence is predicated on a shared identity between the authority and the group members who are the targets of influence (Tyler, 2001).

Coercion, on the other hand, is a form of influence that is exerted across group boundaries, when there is no a priori shared identity between the influencer and target (Haslam, 2004). Coercion is antagonistic to the need for autonomy, frustrating the need to be seen as competent and in control (Tjosvold & Sun, 2001). Turner (2005, p.13) suggests that coercion is inherently a conflictual attempt at control adopted only when other forms of influence are not available – it is the “power one uses when one? does not have power”, that is, when persuasive and authority-based paths to influence are not available (see also Kumar, 2005). Whereas persuasive normative influence and authority-based influence are forms of power exerted through people, coercive influence reflects power over people, by virtue of capacity to deliver on threats. It may be effective in exacting short term and/or superficial changes in the target but the maintenance of any such changes involve continued coercion and/or surveillance which further constrain the freedom of the target and frustrate needs for autonomy. For example, coercive strategies have been observed to be counterproductive to compliance, provoking hostility and aggression while reducing willingness to engage in co-action (Hausman & Johnston, 2010).

People will accept and enact the vision of an authority (as a form of authority-based influence; Turner, 2005) when that authority fosters a shared sense of identity between themselves and the group. Coercive tactics makes salient disagreement with and difference from the source (i.e. an intergroup divide), promoting private rejection even if it elicits public conformity.

Deductive paths to shared identity: identity leadership and change.

Our analysis thus far focuses on the shared relationships between authority and groups, as well as the strategies that leaders can use to position themselves relative to the group and shape the thoughts, feelings and beliefs of people based on persuasive or authority-based influence. Yet our analysis is also limited on two points: first, it has tended to discuss the role of identities as entities that already exist and we have not yet directly addressed the influence processes via which new groups may form. Second, influence does not simply flow “top down”. Group members themselves play an active role in communicating, contesting and shaping group norms (Postmes et al., 2005). In that sense, social influences can be deductive (i.e. group members can ‘take on’ the norms and values of a group that they identify with based on information available in the social context) or inductive (i.e. group members can directly influence each other through social interaction, Postmes, Spears, et al., 2005; Postmes, Haslam et al., 2005). Both routes to identity-based influence provide a basis for engaged, autonomy-supportive influence and cooperation (even in multi-party negotiations; Swaab et al., 2008) but the process is quite different.

What are the processes through which a higher order identity can be used to shape effective persuasive and authority-based influence? Haslam (2004) highlights that – even in negotiation situations where negotiators can choose between coercive threats and persuasive promises – finding ways to identify and craft a higher-order shared identity between two conflicting groups is the most positive way to manage conflict and promote cooperation. Importantly, the most successful strategies will build a higher-order identity based on recognition of meaningful sub-groups: for example, Australia and New Zealand may be two separate democratic nations, with their own strengths, roles and perspectives, but they share a commitment to (and identification with) a rules-based order.

An effective way of exerting influence is to craft a higher-order social identity between two groups but these should still incorporate meaningful recognition of the strengths and unique attributes of the sub-groups.

Research on identity leadership – that is, the process via which a leader or authority is able to actively shape followership via a sense of shared social identity (“we and us”) – highlights four key dimensions that inform the construction and maintenance of a shared social identity between leader and follower (e.g. Steffens et al., 2014). These are summarised in Table 4.

Authority-based influence will be more effective where that authority is seen to represent the unique qualities of the group, actively seeks to benefit the group (versus themselves or other groups), cements the reality of the group, and delivers structures that improve the lives of group members.

Inductive paths to shared identity: grassroots influence and change.

The inductive pathway of influence suggests that influence can flow horizontally such that the characteristics of individuals within the group actively influence and shape a novel, emergent or new group. Under these circumstances, idiosyncratic attitudes and beliefs (i.e., aspects of a person’s personal or individual identity) – shared with other group members via interaction, discussion and debate – form the basis for shared self-definition (i.e., social identification; “we are a group who oppose vaccination”). This inductive pathway to social identity formation implicates a critical role for (online and face-to-face) interaction as the engine room of psychological group formation.

Smith, Thomas and McGarty (2015; also Thomas et al., 2010; Thomas, McGarty & Mavor, 2009) developed these insights and applied them specifically to understand the role of grassroots, novel or ‘emergent’ social identity formation in the context of social movements. They propose that new shared social identities develop when people are motivated to communicate their opinions and ideas about how the world should be. That is, alongside identities based on nation, ethnicity or community, people can also identify with groups based on their opinions (opinion-based groups, Bliuc et al., 2007). Thus, people can be pro-vaxx, or anti-war and, when they do identify with such groups, all of the consequences of such psychological commitment apply: people will tend to be persuaded by people who share their group membership (ingroup members) and behave in line with group norms (e.g., vaccinate one’s children, disseminate anti-war information).

Moreover, when people discuss their opinions about “how things are” (i.e., the status quo, the prevailing norms and standards) and “how things should be” (i.e., their desired social change, how things could or should be), and these are aired, shared and validated with other people through social interaction (discussion and debate), it forms the basis for novel, emergent social identities based on those opinions (e.g., pro- or anti-vaxx; pro- or anti-war). Through communicating ideas about some desired state of affairs, “people can convert those ideas from subjective personal perceptions to socially validated and socially shared cognitions” (Smith, Thomas et al., 2015, p. 544), and in doing so form new identities that provide a psychological basis for influence and co-action.

Table 4. Dimensions of effective identity leadership.

|

Identity leadership |

Definition |

Application |

|

Prototypicality |

Being one of us. An authority that represents or encapsulates the unique qualities that uniquely define that group. |

An authority that is seen to represent the unique qualities that define the group will be more influential. |

|

Advancement |

Doing it for us. A leader or authority who is working to promote our collective interests and goals. |

An authority that is seen to be seeking to advance the shared interests of the group will be more influential. |

|

Entrepreneurship |

Crafting a sense of us. Leaders actively seek to develop and maintain a sense of “who we are”, as well as define group norms, values and beliefs that provide meaning to group members. |

An authority that is able to bring people together in such a way as it crafts a sense of who “we” are and who we are not will be more influential. |

|

Impresarioship |

Making us matter. The capacity of a leader to deliver concrete outcomes for the group. |

An authority that delivers structures, events and activities that help to organize the group’s existence will be more influential. |

Influence is not merely top down but can also flow horizontally between citizens who, together, can discuss and debate how the world should be. Such interactions are important because they provide the basis for group formation (i.e., inductive social identity formation), that is, such influence processes enable new groups to form, to bring about, or challenge a desired state of affairs.

Summary and overview of micro-level influence

Our analysis of influence highlights the interplay between thought and context, but also the interaction between the content of the influence-attempt, characteristics of the source and audience member as well as the relational qualities that explain who source and audience are two each other. Influence involves more than just cognitive information processing (i.e. as reflected in the need for mastery). While the need for mastery examines the cognitive pathways to and factors in influence, the relatedness need highlights a core social dimension. Influence flows within group boundaries and, in this way, identity is the conceptual and psychological link between social context “out there” and effects on the thoughts, feelings and behaviour of people. The need for autonomy signals the need to understand not only the group memberships at play but also the role of power.

Identities are multi-faceted and apply at multiple levels. Every person has multiple identities – spanning micro, meso and macro – reflecting a variety of ways in which individuals are connected with the social world and vice versa. Each of these needs (mastery, relatedness, autonomy) can ostensibly relate to people as individuals and/or group members (i.e. members of communities, organisations, and nations). Effective situational awareness must take into account the factors identified here.